You might think you know what’s rhythm, but you actually don’t.

I studied classical music from the age of 8, and rhythm was always something that was barely touched.

Everything was all about intervals, scales, chords, and keys.

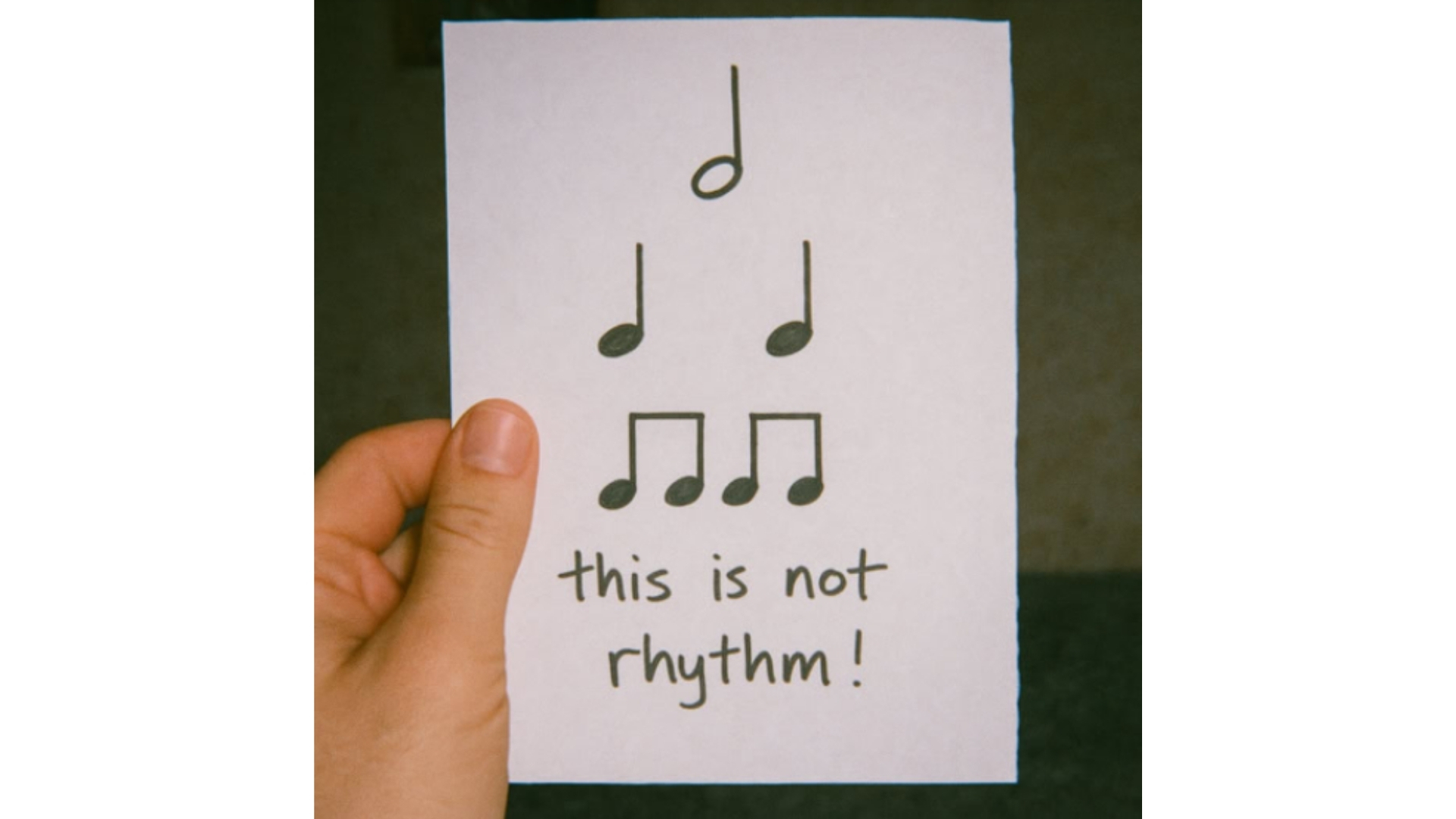

And even when they did talk about rhythm, it was all about “calculating” the placements of notes with rhythm values (quarter notes, eighth notes, etc.) to be able to play a piece of music from sheet music.

Now you might think “but that is rhythm”. That’s exactly what I thought, until I realized that it isn’t.

Like everyone else, I accepted it as a “truth”, and didn’t question it for many years.

After all, I could PLAY rhythm using this method.

And don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing wrong with “calculating” rhythm by counting rhythm values… if you only PLAY music.

The problem comes when you want to COMPOSE music. Because it took me a while to realize, rhythm values only show us the length of the notes, but they don’t help us understand rhythm.

When I started to learn jazz music at 16, it was again, all about scales, chords, and keys, and zero mention about rhythm.

When I tried to compose for jazz big bands at the age of 19, I asked drummers how to create certain rhythms, they only gave me exact copy-paste patterns.

When I received a book about how to play Latin music on piano, it was also about copy-paste patterns.

But here’s what I realized: I never heard any of those patterns in any of the recordings. I remember sitting there with headphones, comparing the notation to the real song, and they just didn’t match.

I was listening to Cuban music, and nobody ever played those exact drum and piano patterns the books told us to do.

So rhythm was either about following exact copy-paste patterns, or something random that you just had to “feel”.

And if you ever felt like that those copy-paste rhythm patterns make your music very generic and cookie-cutter, you know what I’m talking about, and you probably also feel that something’s wrong with this approach.

And don’t get me wrong – you do need to feel rhythm, and you do need to use your intuition. But that’s also true to chords and melodies, yet we have a complete system and tons of theories for those, but not for rhythm.

The reason I could figure this whole thing out is because I followed a really good advice from one of my jazz teachers: “everything’s on the recordings, you just need to listen”.

So somehow, as a Hungarian jazz musician, I started to be interested in traditional Cuban music, and especially timba.

(Timba is a modern Cuban style of dance music that mixes salsa, funk, and Afro-Cuban rhythms.)

And it looked extremely complicated, especially in rhythm. So complicated, that it felt like chaos. But I knew it couldn’t be chaos if it sounds good, and people DANCE to it.

I knew there MUST BE a pattern that everyone follows.

So I started to write down what the bass plays, what the trumpets play, the piano. Especially what rhythm they play.

Because I already knew all about keys and chords, but I knew nothing about rhythm. (Which I only realized when I actually learned what rhythm is.)

Because rhythm isn’t about the length of the notes (the rhythm values); it’s about where you place them on a timeline.

And that realization is exactly what helped me understand rhythm.

After writing down hundreds of songs, I intuitively figured out that they follow a pattern.

And I think I was able to recognize this pattern because I was focusing on those starting points, not on note lengths. In fact, I completely neglected rhythm values.

And the other thing that helped me find this pattern is that I approached every single instrument as a percussion instrument, even vocal melodies!

(Because yes, even vocal melodies have rhythm, not just drums!)

But this pattern I found is not a simple copy-paste pattern, it’s more like a system. And every single instrument – the piano, the bass, the vocal melodies, the trumpets follow it.

I called this a “map” for rhythm and used it to compose my first songs.

So I realized that rhythm is not about copy-paste patterns, and it’s also not completely random.

It’s very similar to the 12-tone system, the 7 notes of a key, and the pentatonic scales, and all these stuff that’s connected to tonality. You can absolutely create music without learning any of these theories, but it’s so much easier to know them, right?

Think about the C major key. It’s also a system, but for tonality. If you write a song in C major key, you don’t necessarily use ALL the notes of the key, right? And especially: you don’t use all the notes at the same time.

And you can write millions of completely unique songs in the same key. They don’t necessarily use the same chords or same melody notes, but they use the same system – C major key.

On top of that, you might even use notes from OUTSIDE the C major key.

Yet when there’s a song in C major key, everyone feels that it’s the same tonal system.

This is very similar to how this rhythm system works.

At first, I didn’t realize the importance of this. But when I started to do research on the internet, I realized: NOBODY talks about this.

But here’s where it gets more interesting.

After I “memorized” this rhythm system and used it intuitively, I started to hear it everywhere.

In modern songs. Songs from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, songs from James Brown, songs from Pharrell Williams, songs from Ed Sheeran, from Kygo…

Yes, the rhythm system I discovered in traditional Cuban music is literally everywhere. In Funk, in Pop music, in EDM, in Jazz.

That’s when I realized that this rhythm system is not just for Cuban music… it’s absolutely universal.

I realized that I’m probably the only one who cracked the code for rhythm. When I realized this, I even told my wife that I’m the only person on the planet who knows about this, and it felt HUGE.

This was around 2013, and since then, I analyzed thousands of songs, and this system is still used in 2025 top hits.

In 2014, I published the theory in a book in Hungarian, and in 2021 I published the English version, and named it: The Rhythm Code.

Since then, more than 18,000 people from 156 countries purchased the book, including a musicology professor who teaches from my book at university level musicology now.

He said:

“It was my students who discovered you… After a short research, I realized that it is a really advanced approach and that we do not use this approach in any way in standard music education. It was both surprising and exciting to realize the musical elements that have been right in front of our eyes all these years but we had not realized.”

Some people who haven’t read my book are skeptical, and I understand why. How likely is it that a “nobody” could discover something this big, something so fundamental?

All those highly educated, world-famous musicians, drummers, professors… and nobody noticed it?

I asked myself the same question many times.

But then I realized, that’s exactly how every discovery starts, with one person who simply refuses to accept that “everything’s already been figured out.”

One person who notices that something is wrong with what’s been accepted as “truth”.

You might think you know what’s rhythm, but you actually don’t.

Tamas Bodzsar

Music Producergram